A new archive and learning zone dedicated to the disability arts movement is set to inspire a new generation of young people to fight for their rights.

The National Disability Arts Collection and Archive (NDACA) facility was launched last week at the High Wycombe campus of Buckinghamshire New University, and features more than 3,500 pieces of artwork, most of which is stored in digital or physical form in the archive.

It is the first study space to be dedicated to learning about the disability arts movement, and it includes both an archive repository and the NDACA learning wing, which features original pieces from the disability arts movement.

The idea behind the learning zone was to create a physical experience that recreates what it was like to be involved in the early years of the disability arts movement in the 1980s and 1990s.

The hope is that it will encourage both disabled and non-disabled people to learn more about the movement’s contribution to the fight for rights and to changing how disabled people are viewed by society.

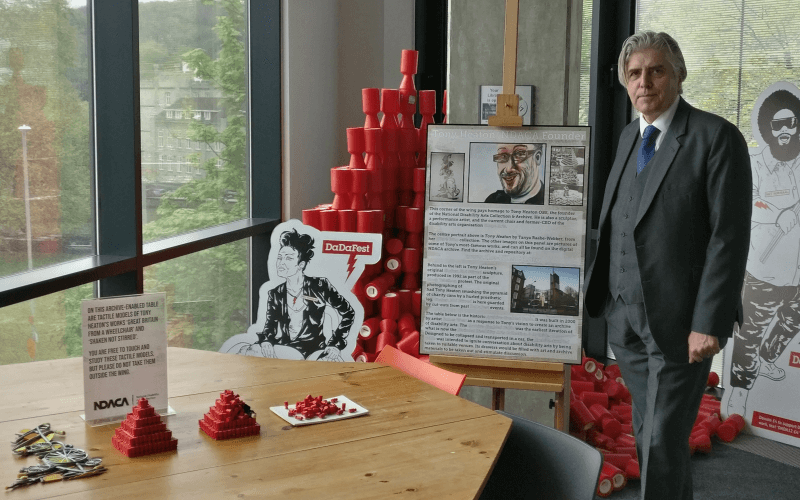

So there are artefacts such as Tony Heaton’s Shaken Not Stirred sculpture, which has been recreated using the original charity collection cans, and which played a key part in the 1992 Block Telethon protest against ITV’s charity Telethon and its “patronizing position of disabled people as pitiful receivers of charity”.

There are photographs and newspaper cuttings from the direct action protests of the Campaign for Accessible Transport, which helped lead to the first Disability Discrimination Act in 1995.

There are also copies of every edition of Disability Arts in London (DAIL) magazine, which was published by London Disability Arts Forum – set up in 1986 to provide a cultural wing of the disabled people’s movement – and a library of books and other literature.

And visitors can take away free tee-shirts with slogans from the disabled people’s movement, such as Piss On Pity and Proud Angry Strong, and Tear Down The Walls and Not Dead Yet fridge magnets.

There are also hydraulic desks for wheelchair-users; a chill-out room, featuring NDACA cushions; and tactile versions of Heaton’s Shaken Not Stirred and Great Britain from a Wheelchair sculptures.

The archive room includes almost all of Tanya Raabe-Webber’s Who’s WhO collection of portraits of leading disabled figures, tee-shirts donated by activists who took part in disability rights protests, and boxes and boxes of other artefacts, such as magazines, postcards and photographs.

The opening of the learning zone and archive room is just the latest stage in a project that stretches back more than 30 years to conversations between Heaton, NDACA’s founder, and fellow disabled artist Allan Sutherland about the need for a collection and archive that would capture the history of the disability arts movement and ensure that key artefacts were not lost for ever.

A 364-page timeline of the disability arts movement, written by Sutherland, will soon be added to the NDACA website and will be available to download, while there will also be a physical copy of it in the NDACA learning zone.

The close links between the disability arts movement and the wider disabled people’s movement are clear throughout the NDACA wing.

There are exhibits such as a framed copy of Vic Finkelstein’s Fundamental Principles of Disability, and a black and white photograph featuring many of the movements’ leading figures, such as Barbara Lisicki, Colin Barnes, Alan Holdsworth, Vic Finkelstein, Sutherland and Heaton, Mike Oliver, Anne Rae, David Hevey, and Adam Reynolds.

Students and staff at the university will use the facilities for their own learning and teaching, while postgraduate students from other universities are already visiting the collection.

Members of the public will also be able to visit the NDACA learning zone by booking in advance, and can make appointments through the NDACA website.

There are also plans for artefacts from the archive, including some of Raabe’s portraits, to tour the country and hopefully be exhibited internationally.

Hevey, the NDACA project and creative director and chief executive of Shape Arts, which is delivering the project – whose photography features in the archive – said the message of the learning zone was “simple but not simplistic” and about the removal of barriers in society.

The NDACA wing is, he said, “full of character” and “a space in which you can feel the power of the disability protest movement”.

The disability arts movement helped to make disabled people more visible in society, he said, and helped usher in the Disability Discrimination Act in 1995.

He said: “It challenged society, achieved great social change and inspired a remarkable body of creative work.”

Hevey, probably best known for producing and directing BBC’s 1997 ground-breaking history series The Disabled Century, said the success of the disability arts movement was “clearly a message to contemporary disabled people facing barriers and fighting for justice and fighting reactionary positions and austerity”.

He said: “We want people to say, ‘Yes, disabled people are winners and they can change the world.’

“If this helps to contribute to the fight against austerity, that’s OK by me.”

He added: “Victories are worth promoting. I think it will inspire a new generation to say, ‘If they can win, we can win.’”

Funding for the project has mainly come from the National Lottery Heritage Fund – which contributed more than £850,000 – with other funding from Arts Council England and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

The NDACA project has already seen the launch of its interactive website, which allows visitors to access digital copies of some of the movement’s most significant work, read essays about significant disabled artists, and by the end of this year will also feature about 50 short films.

Heaton said: “The learning wing is the realisation of a dream I had more than 30 years ago – to collect the unique heritage, and demonstrate the power, of the disability arts movement.

“One that fought barriers, helped change the law and made great culture about those struggles.”

Alex Cowan, NDACA’s archivist, has worked with significant figures in the disability arts movement over the last three years to identify “standout material” from their personal collections.

He said: “I am proud to have been able to participate in a cultural movement that has shaped British art, society and politics and to have played my part in highlighting disabled people’s long struggle for individual and collective recognition.”

The university’s link with NDACA originally came through the music theatre company Signdance Collective, which was previously the university’s resident theatre company.

The university has other close links with the creative and cultural industries, and three of its film and television production students have worked voluntarily as runners on some of the short films produced as part of the NDACA project.

Professor Nick Braisby, the university’s vice-chancellor, said: “We are proud to host the NDACA wing, which represents the significant importance of the disability arts movement and all that it achieved.

“We look forward to welcoming researchers to the university, and giving our students and staff access to the archive which will inform our curriculum and teaching across our course portfolio.”

Stuart Hobley, head of the National Lottery Heritage Fund, London, said NDACA was “a major milestone for disability heritage”, with its “stories of ordinary people who led extraordinary lives and changed the UK’s arts and political landscape”.

He said: “A core aim of all National Lottery funded projects is to make heritage accessible to as many people as possible and this archive and learning wing is a fantastic example of how this can be achieved.”

Picture: David Hevey in the new NDACA learning zone

A note from the editor:

Please consider making a voluntary financial contribution to support the work of DNS and allow it to continue producing independent, carefully-researched news stories that focus on the lives and rights of disabled people and their user-led organisations.

Please do not contribute if you cannot afford to do so, and please note that DNS is not a charity. It is run and owned by disabled journalist John Pring and has been from its launch in April 2009.

Thank you for anything you can do to support the work of DNS…

Welsh government’s disability rights plan ‘is a smokescreen’ to hide lack of teeth and targets

Welsh government’s disability rights plan ‘is a smokescreen’ to hide lack of teeth and targets Cautious welcome for Arts Council England report that shows striking increase in disabled leaders

Cautious welcome for Arts Council England report that shows striking increase in disabled leaders Watchdog shows UK has taken zero action in response to UN recommendations in six areas of disability rights

Watchdog shows UK has taken zero action in response to UN recommendations in six areas of disability rights