The high court has this week been asked to consider evidence of the “unbearable” and “catastrophic” impact of the government’s “fitness for work” system on people with experience of mental distress.

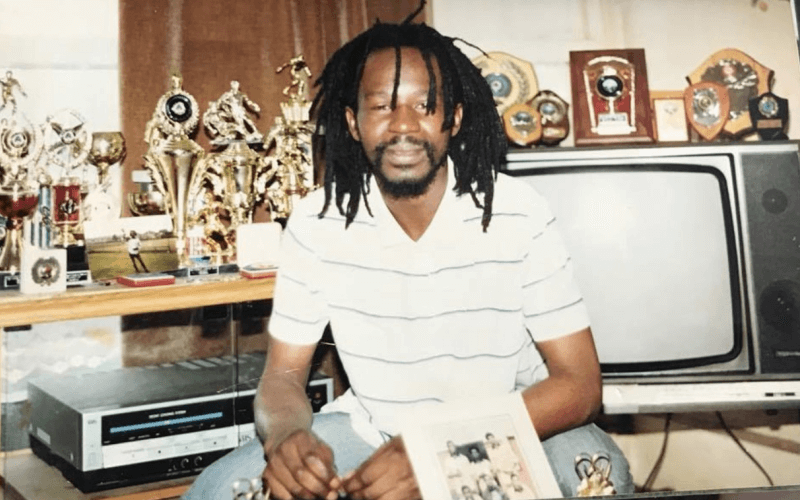

The evidence was submitted to the high court in support of a judicial review claim being brought by the family of Errol Graham (pictured), who starved to death in June 2018 after his employment and support allowance (ESA) was wrongly removed.

A two-day hearing this week heard evidence to back the family’s claim that the decision to halt his ESA in 2017 was unlawful because it breached the Equality Act and the government’s own ESA regulations.

The family are also arguing that the ESA safeguarding policy of the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) on terminating benefits is still unlawful, despite changes made after they began their legal fight.

The claim is being brought on behalf of the family by Alison Turner, the fiancée of Graham’s son.

Errol Graham had missed a fitness for work assessment and had failed to respond when DWP tried to contact him by phone and in person.

But DWP went ahead and stopped his ESA without trying to contact his family or public bodies or considering whether his known history of mental distress could have been the reason for his failure to respond.

When his body was found, he weighed just four-and-a-half stone, there was no food in his flat and no credit on his gas or electricity meters, while an unsent letter to DWP was found which pleaded: “Please judge me fairly.”

The mental health charity Mind provided a witness statement in support of the family’s judicial review claim, which includes testimony from benefit claimants with similar experience of mental distress – and the barriers within the system – to Errol Graham.

One described to Mind how they struggled to eat and sleep and had several panic attacks a day before every face-to-face benefit assessment.

They said in response to a 2018 survey: “I just could not face the thought of the DWP because of the power they had over my life.

“This stress led to me considering self-harm and suicide, which I had previously attempted and been hospitalised for.”

Another said, in response to a 2019 survey: “This is my third assessment in the last four years.

“All I can say is my mental health has deteriorated since these assessments started. I literally lived in fear of the letter arriving.

“I find the questions on the form utterly degrading and hate that I can’t fit into those boxes.

“They also bring about a deep sense of shame about not working.”

Others described how they avoided opening correspondence from DWP, with one saying in 2018: “Just the sight of a ‘brown envelope’ sends me in to a huge panic and I can often put off opening a letter in a brown envelope.

“If I were to use words and phrases such as ‘catastrophic thinking’ and ‘panic attacks’ you may get a fair idea of the way and route that this affects me.”

Mind told the court in its statement that it frequently heard from people who have had significant deteriorations in their mental health after their benefits have been stopped.

One said in 2017: “I stopped spending money on food and heating to save for an uncertain future and relapsed terribly with anorexia.

“I had to give up my voluntary work and go into hospital as I was physically and mentally very unwell: the admission lasted a year – costing hundreds of thousands of pounds which I feel terribly guilty about.

“But if I had felt more supported to take recovery at my own pace, and not feared financial repercussions and sanctioning, then I do not think (nor do my medical team) that I would have relapsed at that point.”

Ayaz Manji, a senior policy and campaigns officer with Mind, who wrote the statement, said the charity continues to hear from local Mind charities whose advisers say they are “fearful about what is happening to people in similar circumstances to Mr Graham who do not have access to the same kind of help”.

Turner said before the hearing: “The DWP decision to stop paying Errol’s benefits meant that, without money to buy food and to pay for heating and lighting, in the end, he starved to death.

“Although at first the DWP maintained that their safeguarding policy was lawful, faced with a court case, they have made some changes to the policy.

“But these changes are not enough. It still falls to the vulnerable claimant to make sure the DWP knows why they have good cause not to respond to DWP enquiries.

“That makes no sense when vulnerable claimants might be too mentally ill to respond.

“For Errol’s sake, I have to challenge this policy so that other people don’t suffer in the way that he and our family did.”

Tessa Gregory, from legal firm Leigh Day, who represents the family in their claim, said: “The DWP provide support to many others like Errol, who due to their significant mental health issues may miss appointments and may have difficulty responding to correspondence.

“It cannot be right that it falls to such vulnerable individuals to prove that they had a good cause for not responding and the DWP must require their staff where necessary to make further enquiries before taking the momentous decision of cutting off what is often a person’s only source of income.

“Unless and until the DWP changes its policies other vulnerable individuals will remain at risk of serious harm or death.”

The Equality and Human Rights Commission, which is intervening in the case, has made it clear that it agrees with the arguments put forward by Turner’s legal team.

It also makes further points of its own, including highlighting the importance of article three of the European Convention on Human Rights – which prohibits inhuman or degrading treatment – and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Judgement has been reserved until a future date.

A Department for Work and Pensions spokesperson said: “Our sympathies are with Mr Graham’s family.

“It would be inappropriate for us to comment further at this time.”

A note from the editor:

Please consider making a voluntary financial contribution to support the work of DNS and allow it to continue producing independent, carefully-researched news stories that focus on the lives and rights of disabled people and their user-led organisations.

Please do not contribute if you cannot afford to do so, and please note that DNS is not a charity. It is run and owned by disabled journalist John Pring and has been from its launch in April 2009.

Thank you for anything you can do to support the work of DNS…

‘Disastrous’ cuts bill that leaves legacy of distrust and distress ‘must be dropped’

‘Disastrous’ cuts bill that leaves legacy of distrust and distress ‘must be dropped’ Silence from MP sister of Rachel Reeves over suicide linked to PIP flaws, just as government was seeking cuts

Silence from MP sister of Rachel Reeves over suicide linked to PIP flaws, just as government was seeking cuts Disabled activists warn Labour MPs who vote for cuts: ‘The gloves will be off’

Disabled activists warn Labour MPs who vote for cuts: ‘The gloves will be off’